Review: Fritz Lang's M

by Lucy Johns, SF Art & Film mentor

It’s still early in the history of cinema. Of the basic technological elements of the new medium – movement, sound, color, the artifice of imagery – only movement is firmly in place. Sound has just appeared. Where is precedent for blending sound and movement? Opera. In Fritz Lang’s “M,” one of the first films out of Germany with sound track, sound is on show, along with a sensational story.

A city of four million is gripped by the horror of a serial child killer. Music introduces the specter in the opening frame as a child sings a lilting threat of kidnapping by a man in black. A mother carrying laundry shouts for her to stop. She doesn’t. When the little singer becomes the next victim, the stage is set for conflict between society and a monstrous outcast who looks, unfortunately, just like everyone else. The police proceed with huge sweeps and household intrusions. The criminal underworld, maddened by the excessive attention, organizes its own troops, including a union of beggars, to find the killer before business is shut down completely. All are stymied until a sound proves the trap that catches the killer.

Building on Wagner’s invention of the musical theme that symbolizes a particular character - the “leitmotif” – “M” introduces the killer with a snatch of “Peer Gynt” whistled as only his hand, writing a taunt to the police, is visible. While the director explores the dramatic potential of tiny sounds (the tap tap tap of a knife hammering a nail) and of long silences overlying strong movement (dozens of men fanning out, soundlessly, through city streets), the killer’s leitmotif pulls the story to its fitting end. It is a masterful irony for film as a visual medium that the killer is caught by a man who cannot see but who recognizes that leitmotif and follows it.

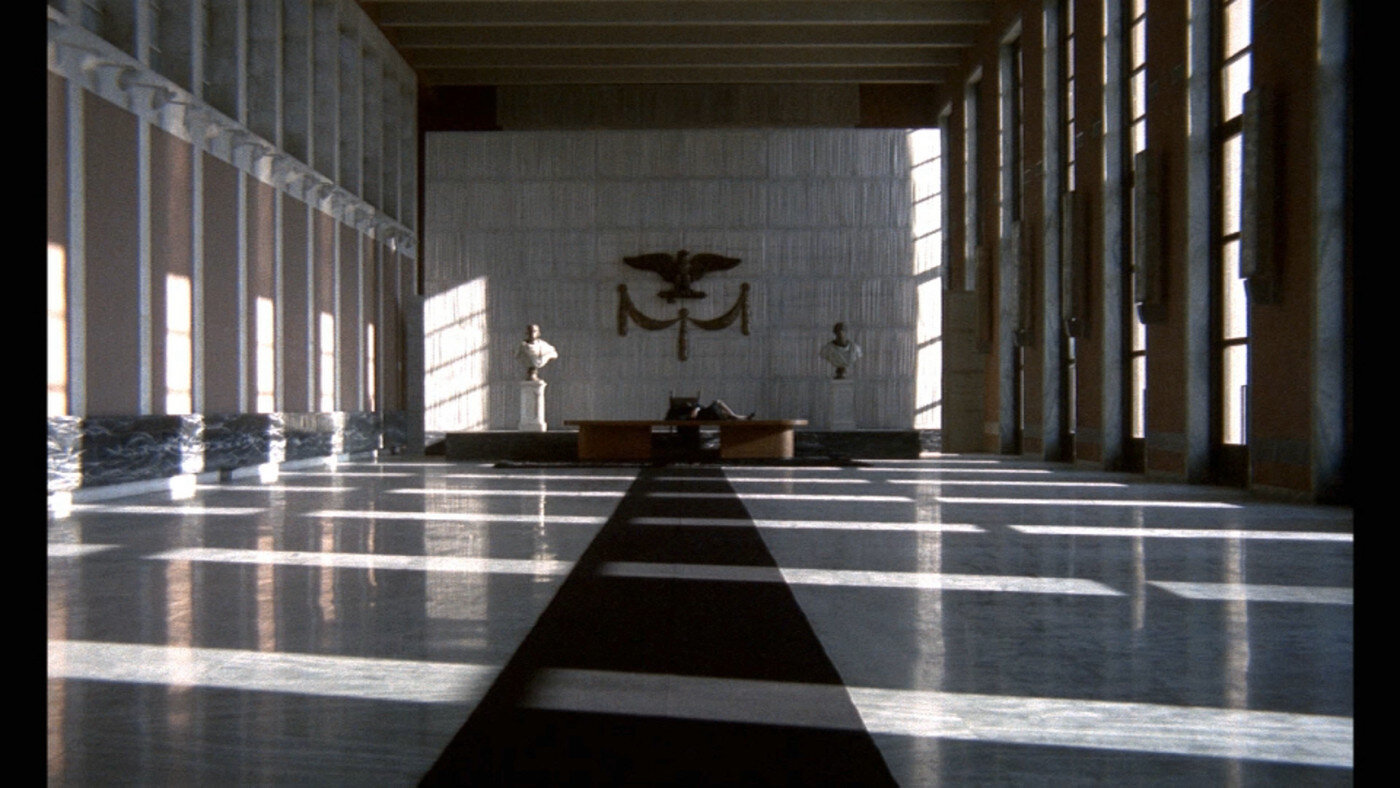

“M” also remains gripping after 80 years thanks to its imagery of the chase and the intellectual challenge of its penultimate scene. As the criminal gang closes in on a vast building, the killer hides amidst dark storage rooms whose open-bar front grills make looking out easy while foiling looking in with shadows and clutter. This complicated interior that connives with bad guys to obstruct good guys became a staple of crime and horror films to come. The people’s court that finally grapples with the killer’s anguished confession might as well be a contemporary jury confronting the alleged etiology of a similar heinous crime. Peter Lorre’s operatic monologue pleads the case for sickness vs. depravity as vividly as one could wish, to as little avail then as now. “M” is an artistic milestone presenting an ageless morality play.